It was a no-brainer if there ever was one. For the 1981 model year, Polaris dropped its existing Centurion 500 liquid-cooled three-cylinder engine into the revolutionary Indy chassis that had been introduced the year before to create the Centurion Indy 500.

Polaris already had car racing legends Bobby and Al Unser available to promote the new machine, and they had won the world-famous Indianapolis 500 no less than five times between them. Plus Bobby had been one of the pioneers of the sprint car-style ski suspension used on the Indy, so the new Indy 500 concept went together so well that it was downright scary.

A Technological Tour de Force

As the first three-cylinder “suspension” sled available to the public, the Polaris Centurion Indy 500 was a technological tour de force of snowmobile engineering, with best of breed engineering almost everywhere.

The Indy chassis was the culmination of three years of Polaris race team development in the late 1970s. The ski suspension used a leading arm (incorrectly referred to ever since as a trailing arm) concept with dual parallel radius rods, a sway bar and coil springs over hydraulic shocks to produce 6 inches of smooth, bump-devouring travel.

Exhibiting superior ride quality and handling at speed, this suspension was clearly light years ahead of leaf springs, swing arms, telescoping struts and anything else that had ever been used in the sport to this point.

Moreover, Polaris had long been known for its smooth, easy shifting clutching that delivered power to the track with greater efficiency than anyone else’s pulley system. And the Indy’s jackshaft drive distributed forces in the riveted aluminum chassis better than the old-fashioned practice of mounting the driven pulley on the chaincase.

The existing Centurion three-banger was a very straightforward piston-port design with Mikuni slide valve carbs, a compact three-into-one exhaust, and nothing exotic other than the extra jug. But that extra cylinder was visually imposing any time the hood was opened – sort of an “I’ve got more than you’ve got” statement. The engineering advantage of the extra cylinder was room for more port area in the cylinder walls for better breathing efficiency. These engines also tended to be pretty good on fuel in sustained cruising, and many riders loved the unique sound of the triples.

In back the Indy 500 had a slide rail suspension with a claimed 7 inches of travel that was very competitive, if not industry-leading, and an all-rubber internal drive track when steel-cleated tracks were still in use elsewhere. Finishing touches included a hydraulic disc brake when most competitors were still using a mechanical one and a 120-watt alternator that put out better-than-average electrical power.

Satisfying But Uncompetitive

The Indy 500 triple proved popular with owners who purchased the sled for its performance potential. Snowmobile magazine’s Official Owners’ Survey reported that “It’s obvious that there have been a lot of radar guns pointed at the Indy 500 … since many owners noted that top speed was radar-certified. And with the average of 94-plus mph, it’s obvious that people who own 500 Indys squeeze that throttle occasionally.” Owners also noted superior handling on the trails at high speed, with a number of comments about “never going back to a conventional front suspension.”

The biggest negative noted was weight that contributed to the sled feeling very heavy. Other negative comments were made about the minimal storage space and “idiot light” engine temperature indicator. Many owners also wanted a front bumper to make it easier to handle the sled. Still, overall satisfaction scores were high, with 92 percent of the respondents saying that the Indy 500 met their expectations.

So how did the Indy 500 triple stack up against other models? The December 1981 Dayco Muscle Machine Shootout pitted a dozen factory-backed muscle sleds from all eight remaining brands against each other in the industry’s first big snocross event at Alexandria, Minnesota. The best Indy 500 finisher was Guy Useldinger in fifth place, beaten by an Arctic Cat El Tigré 6000, an Indy 340, a Scorpion Sidewinder and a Ski-doo Blizzard MX. All but the Cat had smaller displacement engines than the Indy 500.

And out on the trails that winter, lighter weight sleds from some of the other brands dusted the Indy 500s in impromptu drags and frozen lake blasts across the Snowbelt. Clearly something wasn’t quite right. The problem was diagnosed as inadequate power for the weight.

Bigger Is Better

The 1982 Indy 500 lost the Polaris Centurion in its name and got the BNG (bold new graphics) treatment, but little else changed as Polaris worked behind the scenes to make its three-banger more competitive.

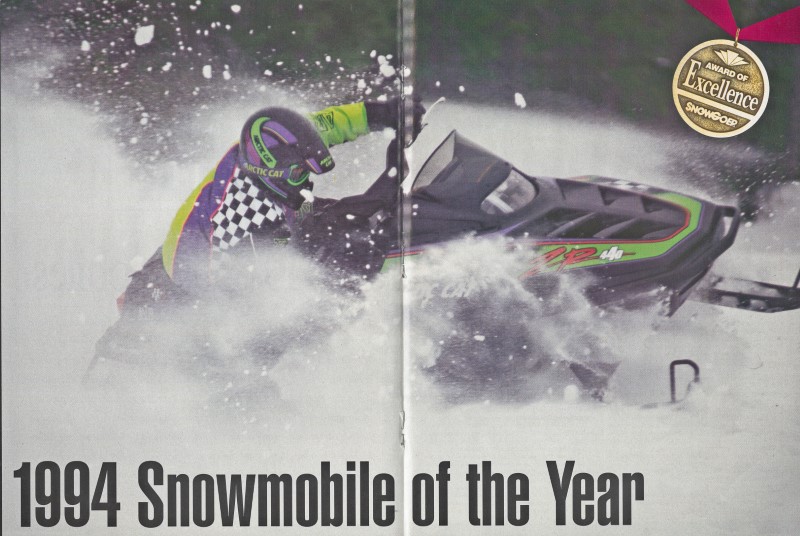

For 1983, the triple received an additional 97cc of displacement to become the Indy 600, a much better performing model that would sell in good numbers before giving way to the even more impressive Indy 650 triple for 1988. Polaris eventually took its triples out to 800cc in the Storm, and all these larger Polaris triples built a solid reputation as powerful engines for drags, lake running and performance trail riding, particularly when modified. The XLT, of course, was a legendary triple that propelled Polaris past 40 percent in marketshare in the mid 1990s.

The Indy 500 triple was quickly forgotten as Polaris moved on, and this pioneering three-cylinder suspension sled is now seldom seen. However, the Indy 500 name would find new life. In spring 1988, Polaris introduced the new 1989 Indy 500 twin with the 488 Fuji that would go on to become one of the most successful snowmobile models of all time. But that’s a story for another issue.