Felix Wankel was first granted patents on the radically unique combustion engine in 1954. The German engineer’s new engine was considered by many to be the powerplant of the future, and wonderful things were predicted for it by almost everyone from the auto industry to lawn mower manufacturers.

Flash forward to 1973. Results failed to keep up with the Lofty expectations, and the number of successful Wankel engine applications could be counted on one hand.

Use of a Wankel or rotary engine on a snowmobile first surfaced in 1968-69 when Arctic Cat, Polaris and Scorpion all offered a Sachs 303cc rotary engine in limited numbers. It produced a meager 15 hp, and all but Arctic Cat dropped it the next season.

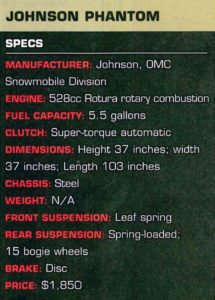

In 1972, Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) created news and excitement by announcing that as part of its ’73 Line it would manufacture Johnson and Evinrude snowmobiles powered by “rotary combustion engines,” as it preferred to call them. One such snowmobile was the Johnson Phantom, considered in 1973 as a luxury machine.

Nearly A Decade Of Development

OMC’s decision to use the rotary combustion engine dated back to the summer of 1964 when engineers were running tests on boats. Both gas turbines and early Wankels were being used, and at that time the big interest was in the turbine.

But engineers discovered during those side-by-side tests that the Wankel came close to matching the turbine in quietness, smoothness and efficiency.

After much thought, a full-scale development program for a rotary combustion engine got under way. Once the engine began to take shape, the decision was made to give its first test in snowmobiles. “The theory was that in the OMC product Line snowmobiles would provide the toughest test bed because of the wide range of speeds, Loads and temperatures that the machines would be run,” Snow Goer editors wrote in 1972.

In 1966 OMC signed License agreements with Curtiss-Wright and NSU Wankel to develop, manufacture and sell rotary engines. In 1972, 150 experimental machines were put to the test, some of which piled on as many as 2,500 miles.

“At this writing there had only been one engine failure; cause not yet determined,” editors wrote in 1972. “And, not one of the new engines had required a plug change. A combination of a high-voltage capacitor discharge ignition (CD) system and a surface-gap spark plug positioned so that the rotor seal wipes across its surface with each revolution had created a snowmobile engine with a Lifetime spark plug.”

So after eight years in planning and developing the OMC engine, trademarked as the Rotura rotary combustion engine, it became the first rotary to be developed, manufactured and marketed in the United States.

Why Rotary?

The rotary engine has considerably fewer moving parts than a conventional two-cycle – there are no pistons or connecting rods moving up and down in cylinders. The body of the rotary engine is a fairly narrow housing with an elliptical-shaped chamber called a “trochoid.” This serves as the combustion chamber. Inside the trochoid is a triangular-shaped rotor, which revolves on an electric shaft. As the three arched lobes of the rotor revolve inside the trochoid, each lobe forms a moving pocket of combustion chamber, separated from those of the other lobes by seals at the points or apexes of the rotor. The intake and exhaust ports are nothing more than open ports in the side of the trochoid.

The OMC rotary engine had several advantages over a conventional powerplant, according to editors; including the use of a super-smooth and tough coating on the trochoid surface that reduced wear. Other advantages included better power to weight ratio and improved torque and fuel consumption.

Sound reduction – a major goal from sled makers because of looming legislation on the horizon – was also a big plus with the Phantom. In fact, one Snow Goer tester described the Phantom as being “as quiet as a vacuum cleaner,” a compliment at the time. “Cleanly taking first in the quiet sweepstakes in Wyoming with a 93 dB [decibels] at operator ear Level at three-quarter top RPM on the dyno, the Phantom is well below all present legislative noise standards,” they wrote. Fewer moving parts, insulation around the engine and a silencer box on the carbs all contributed to less noise.

The Phantom engine produced 35 hp at 5500 rpm, according to Johnson ads. “Just turn the key and you’ll hear the future of snowmobiles. Low… Mellow… Smooth. Now squeeze the throttle and hang on. The sound doesn’t change but the power does. It surges through in a wide range, from low-end to top. More than you need, but there when you need it.”

Snow Goer dyno tests revealed as much. “The Phantom Rotary engine turned out what could be considered an ideal curve of delivered track horsepower on the Hartzell dyno in Wyoming,” editors wrote.

Much More Than A Rotary Engine

The Phantom was described by editors as the Cadillac of snowmobiling. “You wouldn’t wrap Raquel Welch in a granny dress,” they wrote, “and the OMC top brass have housed the Rotura in a first class, top performing snowmobile.”

The wide padded seat and multiple torsion-spring bogie wheel suspension was “impossible” to bottom out, they claimed. Though its weight was not released, it was considered “substantial.” This posed real challenges when it got stuck, though reverse was its “saving grace.”

Besides reverse, the Phantom featured other standard, Luxury equipment such as electric start, neutral, a choke primer, Larger headlights and taillights, speedometer, tachometer, parking brake, and even a cigarette Lighter. Everything on the Phantom – the manual starter handle, reverse lever and the passenger hand-grips – were mitt-sized for added convenience.

If Luxury snowmobiling was what you wanted in 1973, the Phantom was a top choice, editors claimed. “The Phantom is aimed at a specific market; it’s for the man who likes it all done for him, completely safe and manageable.”

Editor’s Note: Every issue of Snow Goer magazine includes in-depth sled reports and comparisons, aftermarket gear and accessories reviews, riding destination articles, do-it-yourself repair information, snowmobile technology and more! Subscribe to Snow Goer now to receive issues delivered to your door 7 times per year for a low cost.

Sorry guys but you’ve got some errors in your article. The Sachs 303 used by Cat from 1968 to 1970 was 18.5 hp and was upgraded by Sachs for the 1971 season to 20 hp. They changed the porting. I’ll be more than happy to show my old dealers notes from the period to anyone who cares to contact me. I’ve owned several over the years and they are a fun little sled. It was not underpowered as compared to most 300cc singles of the period. Arctic made and sold thousands of them. For 1973 they switched to the 24hp KM 24 295 version and when installed in the lightweight Lynx chassis this little gem ripped. There was also an ultra rare 606cc twin that was shopped around but had no takers. Cat built 6 prototype Panthers with this engine in 1968. It was rated at 35hp. Only 1 less than the much bragged about 634 Hirth twin.

I’m good naturedly needling you pros to do better. Any Vintage sled head knows this stuff. Now the generator version of the 303 was low power, they held the speed down to 3600 rpm. The sled version generated its power at 6000 rpm+. Is this where you got your data?