Fifteen years ago in the December 1999 issue of Snow Goer magazine, then-editor Eric Skogman put together this article after paging through past issues of the magazine. Just when he though he found the oddest aftermarket product available, he’d page through another issue and find something even more odd. For Throwback Thursday, we offer this throwback of throwbacks. Enjoy!

It’s the late 1960s, protests are raging across the nation and hippies are making their way to Woodstock in search of peace, love and a little music. At the other end of the specturm, the snowmobile industry is skyrocketing.

While many people tried to cash in on the booming snowmobile market in the late ’60s by building sleds, other entrepreneurs were marketing their products with hopes of striking it rich. Perusing through the faded pages of Snow Goer back issues, it seems everything but snake oil was being advertised.

Many of the products seem legitimate and well thought out. But, there are some that seem a little quirky, maybe even downright ludicrous. These interesting products from the late 1960s and early 1970s- most of which failed- will remain in the faded pages of back issues, except for those highlighted here.

Better Than Blubber

Eskimo Foods of Kasilof, Alaska, advertised its tasty fare in the January 1968 issue of Snow Goer. Even today, the grub sounds mighty good.

Knowing the big appetites snowmobilers get after a long day on the trail, Eskimo foods advertised seal meat, whale meat and reindeer meat. For as little as $4, snowmobilers could enjoy the delight of those meats, and the editors at the time enticed readers to give it a whirl.

“Let’s have every U.S. and Canadian Snow Goer reader try it,” the editors wrote. We don’t know who tried it or how it tasted but our mouths are water thinking about those delicacies. Mmm, mmm, good.

While some were marketing interesting food, others invented products to protect the eyes and faces of riders. Good eye protection is essential for sledders when on the trail, and E.A.I. Limited of Minneapolis, Minnesota, thought it had the solution. Enter the Turbo Visor weather shield. On the surface it seemed like a good idea.

Either attached to a helmet or someone’s head, a big, clear circular shield sat in front of the user’s face. As the wind hit the fins on the outside of the shield, the visor spun like a pinwheel. That spinning motion was supposed to spin off rain and snow. So it not only protected someone’s eyes, but it also cleared away the snow for better vision.

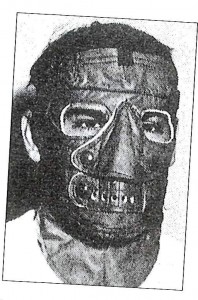

Aside from eye protection other companies had ideas on how to keep riders’ faces warm. Long before Hannibal Lecter made his gruesome appearance in “Silence Of The Lambs,” Owl-Lite Equipment in Fort Erie, Ontario, tried to sell its complete face mask reminiscent of Hannibal The Cannibal.

The mask, made of vinyl with a light felt lining, covered the entire face. The nose piece was removable to clear out snot, and the adjustable head strap made it even fit a blockhead like Charlie Brown.

“It’s ideal for high-speed racing and snowmobiling in extremely cold weather,” the ad chanted. It was probably a good Halloween mask, too.

Cover Yourself

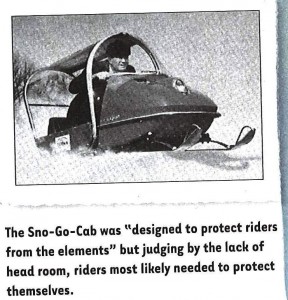

Koehn Manufacturing of Watertown, South Dakota, took a different approach. Instead of covering someone’s face with a vinyl mask or a circular plastic shield, they believed it was better to cover the entire seat and rider with a canopy. The Sno-Go-Cab was “designed to protect snowmobile riders from the elements.”

The clear canopy glided open and closed on special runners mounted near the running boards. A tubular steel roll-bar frame held the canopy in place. The transparent windows were made by Eastman Kodak. The enclosure used engine heat to keep riders warm.

In December 1970, Oxwood Industries of Woodstock, Ontario, believed snowmobiles needed safety deflection bars. The Safety Roll Bar mounted directly above the wind shield and was supposed to deflect tree branches away from the driver. In addition, the heavy duty skid bars ran along the sides of the machine and acted like “outriggers.”

In December 1970, Oxwood Industries of Woodstock, Ontario, believed snowmobiles needed safety deflection bars. The Safety Roll Bar mounted directly above the wind shield and was supposed to deflect tree branches away from the driver. In addition, the heavy duty skid bars ran along the sides of the machine and acted like “outriggers.”

Signal Your Turn

In the late 1960s and early ’70s at least one company believed trail congestion posed problems.

For that company, rigging a snowmobile with automotive-type devices seemed logical. Special Products Company in Meriden, Connecticut, made signal light kits for sleds. The Spec-Pro fit every snowmobile model. The lights could be used as signal, hazard and stop lights.

“Avoid accidents. Be first. Be sharp. Be safe. Amber front and red rear can be seen from rear, front and sides. Be the envy of the club,” the advertisement said.

The front lights mounted to the side of the hood, and chrome brush guards “improved the appearance of all machines.” For sleds with electric start, the light kit was available for $29.95. For manual start sleds, the kit retailed for $39.95.

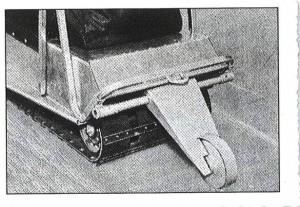

Safety is always a concern out on the trail especially when it’s icy. And S-S-S Manufacturing in Mayville, North Dakota, believed its Sno-Sled Stabilizer would allow snowmobilers to drive safer on ice, as well as other trail conditions. The Sno-Sled Stabilizer mounted to the rear of the sled and dragged on the snow behind the sled. It allegedly eliminated spin outs and fish tailing.

A round device on the end of the stabilizer rested against the snow or ice. This helped stabilize the back end of the sled, the manufacturer claimed. In powder snow, the SnoSled Stabilizer could be locked up and out of the way.

Unlocking it and having it drag behind the sled on icy or hard packed surfaces improved its handling, S-S-S claimed.

“Now operate safely on ice. Avert dangerous skids, spills and collisions on compact snow or ice,” S-S-S Manufacturing stated in its ads.

It could also be used as a “kickstand.” Tension springs held the stabilizer in place. The makers of the stabilizer even tested it on the trails in Yellowstone National Park, according to an advertisement in the February 1969 issue of Snow Goer magazine.

There are many more odd products that leap off the pages of back issues of Snow Goer. But much like the snowmobiles of yesteryear that are seen in the magazine’s Flashback department, the products proclaiming the latest revolution are now a part of snowmobile folklore. And there they will sit forever.