A few years ago my buddy Ron bought an old Yamaha Bravo for his son as a sensible step up from the youngster’s 120. That got me thinking about the little Bravo’s place in snowmobile history. It’s a lot bigger than you might think.

Introduced for the 1982 season, the 31-year run of the Bravo series was unprecedented in Yamaha snowmobile history, and very few models of any brand have lasted longer.

Simplicity On The Snow

Created over a three-year period by Karl Ishima and engineer Toshi Yasui in an unsuccessful attempt to build a sled that could be retailed in the U.S. below the magic $1,000 price point, the Bravo was ingeniously engineered for simplicity and low cost by reducing the number of parts.

For example, the over-square engine’s five-port cylinder and cylinder head were cast as one piece to eliminate a gasket and multiple fasteners. The bolts that held the crank case halves together also secured the motor mounting plate to the engine. Other cost and weight-saving measures included an unusually short tunnel and a short and light track with a unique 4.08-inch drive pitch; a new, lightweight drive clutch; no hood insulation; and no chrome anywhere except on the handlebars. Surprisingly, jack shaft drive was used to keep the center of gravity low.

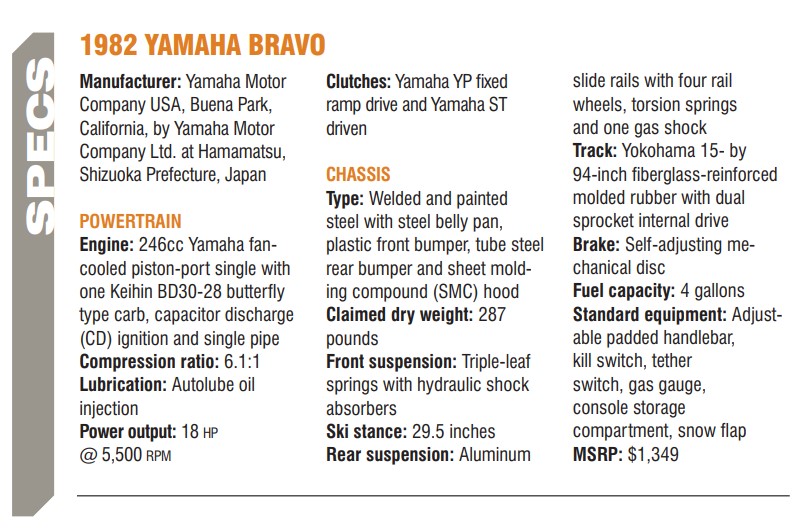

The resulting sled was smaller and lighter than the 250 Enticer that it was replacing in the lineup, but somehow it was still big enough for most people. Top speed was about 50 mph with an average-sized adult aboard, and it was pretty quiet considering the lack of sound-deadening material under the hood. Initial price was set at $1,349 plus freight and dealer set up.

The engineering on the original model BR250F was so solid that only a few warranty updates were needed. The outer steering arms were upgraded, the plate that positioned the steering shaft required improved attachment, and extension caps were fitted to the front of the slide rails to prevent jamming if the track was allowed to get overly loose. But that was it.

Industry magazines fawned over the new Bravo. “This new little sled could well be the start of something really big for Yamaha,” predicted Snowmobile magazine, which put the Bravo on the cover of its October 1981 issue. Snow Goer immediately named it one of the “Best Value” sleds for 1982.“It is frugal in weight, power, and price; and should be just right for first-timers or the budget-minded,” editors said. Even performance-oriented Race and Rally magazine commented that it “gets 40 percent better fuel economy than the 250 Enticer (due to) reduced weight,” and that it “is considerably more quiet than the ET 250 at the driver’s ear.”

After the initial euphoria wore off, however, the Bravo didn’t get much more ink as the more popular performance sleds regained the limelight. But there were a few exceptions. After testing a Bravo at the 1985 Snowmobile magazine Rode Reports, then 15-year old Erik Nicholsen commented that “It had a lot more to offer than I thought it would.”

Big Foot Bravos

The Bravo grew into a model series in the middle of the 1980s when the two longer tracked models were added and aimed at the far north. The Transporter had a 102-inch track and the Trapper utility model got a 136-inch track and a rear cargo rack, but the sleds were otherwise minimally changed. Only the Trapper came to the lower 48 states, where it was known as the Bravo Long Track, and only from 1987 to 1993.

But the long track Bravos proved staggeringly popular in Alaska and northern Canada, and they were also successfully sold elsewhere around the world. Affordable and reliable, Bravo utility models served hunters, fishermen and trappers who relied on the wild outdoors for a living, and they came to rely on the Bravo to help do it. The sleds weren’t fast, but they would go pretty much anywhere, could be easily manhandled when needed, and just kept running and running and running.

Nothing Lasts Forever

Mainstream demand for the little-changed Bravo diminished over the years as coil spring ski suspensions gained popularity, and 1995 was the last year for the base model. The northland-only Transporter departed the market the following season. But the Trapper kept on chugging through the great white north until it was discontinued in 2012. The price had ballooned to $5,299, but that was still dirt cheap compared to much larger and much heavier multi-cylinder four-stroke utility sleds.

Unfortunately some expensive tooling for the Bravo was worn out and Yamaha made a business decision not to replace it. The company also wanted to convert to all four-cycle engines across its snowmobile line, and the two-stroke Bravo just didn’t fit any more no matter how much the people of the far north loved it. So the unassuming Bravo, the best-selling, longest running Yamaha snowmobile model ever made, slid into history to a chorus of complaints from the far north.

Editor’s Note: Every Snow Goer issue includes in-depth sled reports and comparisons, aftermarket gear and accessories reviews, riding destination articles, do-it-yourself repair information, snowmobile technology and more. Subscribe to Snow Goer now to receive print and/or digital issues.