Wheel Horse Products Inc. was formed in 1946 to produce lawn and garden tractors and related outdoor power equipment. But by the late 1960s, it was yet another hard goods manufacturer attracted to the overheated snowmobile market.

With a home base in the Snowbelt, a reputation for quality products and 3,000 dealerships across America selling similarly sized and priced wheeled goods using similar technology, Wheel Horse appeared to be a solid candidate for snowmobile success. It also wasn’t lost on management that several of the company’s direct competitors, including AMF, Bolens, Poloron and Sears, were offering snow sleds as well.

But Wheel Horse officials didn’t display any horse sense, which the dictionary defines as common sense, when they entered the snowmobile business.

Inexplicably, Wheel Horse decided not to engineer its own machine. In April, 1969, the company made an expedient entry into the sled business by purchasing the Sno-Flite brand that had been built for the 1968 and ’69 seasons by the C.E. Erickson Company Inc. (Cee-Co) of Des Moines, Iowa. Cee-Co was a manufacturer of cabinetry, display fixtures and advertising novelties that had also built go-karts, apparently unsuccessfully, and this probably should have raised a red flag for Wheel Horse. But apparently it didn’t.

Sno-Flite To Safari

Sno-Flite was another of the dozens of “me, too” snowmobile brands flooding the market in snowmobiling’s early days. With nothing to differentiate it from dozens of competitive sleds, and hampered by unattractive styling that made the sleds look clumsy and appear heavier than they really were, the Sno-Flite sleds sold very poorly in the intensely competitive snowmobile market.

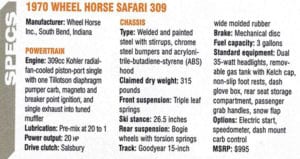

Wheel Horse moved sled production to its tractor plant in South Bend, Indiana, where the workers reportedly experienced considerable difficulties building snowmobiles. Sno-Flite became Safari, with a red color scheme to differentiate the new machines from the yellow Sno-Flites. An air scoop was added to the top of the hood, the front bumper was switched from flat to tube stock and most models got a new rear storage compartment, but the uninspired design was otherwise left pretty much the same.

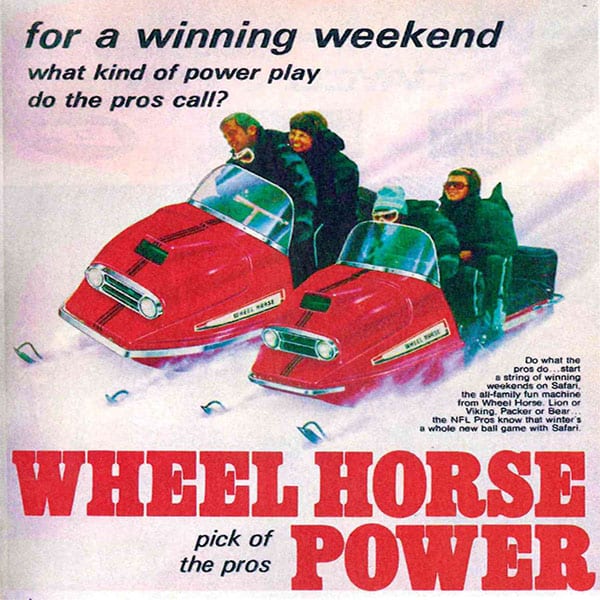

About 2,000 leftover Sno-Flites were remanufactured as Safaris, a common industry practice of the time, and another 4,000 new Safaris were built for 1970. All six models had Kohler engines, ranging from an 18 hp 295 to a 30 hp 440, with five on 15-inch tracks and one with a 22- inch wide track. Positioned as “rugged as any Wheel Horse tractor” and promoted by an NFL endorsement as the “pick of the pros” with a league logo on ads and literature, Safari models were priced from $845 to $1,195.

The company signed up many dealerships with inducements of free freight and free dealer floor plan financing until February 1, 1970. Attractive sales literature, color TV commercials and a big schedule of national magazine ads supported the effort. Dealerships were also encouraged to demonstrate the machines and many did. SnowCo trailers, a leading brand of the day, were also offered as Wheel Horse branded accessories. Retail sled sales were slow, but not totally stagnant.

“We had a single-cylinder, low-horse power Wheel Horse snowmobile,” recalls my long-time riding buddy Wayne Farley. “It was my dad’s. He bought it brand new from our Wheel Horse dealer in town [Avon, New York]. It was the biggest piece of crap you ever did see. Ride it 15 minutes to an hour and it would break something in the suspension – shaft, bearing, this, that and the other thing. The hood was the most incredible thing on it, though. It was some sort of plastic. It got rolled down hills and never got a crack in it. We used to ride with this crew in the neighborhood and we were young bucks, ex-military and all that. We’d go across a field, 25 or 35 miles per hour, next thing you know I’m rolling over. The sled couldn’t go 35 mph without rolling. It was horrible.”

Failure Came Fast

With about 2,500 of the 1970 Wheel Horse sleds unsold at the end of the season, no new Safaris were built for 1971. Rein hard Brothers, the company’s Midwest distributor, bought 2,000 of the leftovers and blew them out in the ’71 season at about half off the suggested retail price with a full one-year warranty, a rarity back then.

The limited production 1972 Safari line was just three models with new decals and a few minor improvements including more power for the wide track, but not even a parts book, just a four-page list of supplemental parts. Sales remained slow, so the company dropped snowmobiles and sold the remaining Safari assets to Parts Unlimited, which supported the brand until the parts ran out.

Wheel Horse showed no horse sense in acquiring the failing Sno-Flite, or frankly for entering an already over-saturated snowmobile market. With barely two years of actual production over a three-year period, the Safari was one of the fastest flops on record for a nationally distributed name-brand snow machine.

The Wheel Horse name departed the lawn and garden industry in 2007, sparking renewed interest in everything with the company’s logo, but decent examples of the failed Safari snowmobile are rare these days because most of them were deservedly junked long ago.

Editor’s Note: Every issue of Snow Goer magazine includes in-depth sled reports and comparisons, aftermarket gear and accessories reviews, riding destination articles, do-it-yourself repair information, snowmobile technology and more! Subscribe to Snow Goer now to receive issues delivered to your door 6 times per year for a low cost.

Bring it back! C’mon Big Red!

Pingback: Top of The Lake Snowmobile Museum: Naubinway, Michigan - Guide2Museums