1984 John Deere Snowfire – Sunset for Free Air Sleds

Free air snowmobile engine cooling was very popular during the vintage era because it offered a lot of advantages. It was light weight and less expensive than any other cooling type due to fewer parts. It was also highly efficient in cold weather, easy to maintain and rebuild, and relatively quiet compared to the often obnoxious whine of an over-driven axial cooling fan.

All of that and more made free air cooling a big hit. It was widely and successfully used by more than two dozen brands, particularly on race sleds and sporty trail performance models.

But as the years rolled on, free air cooling began to fall out of favor. Fully-enclosed hoods for noise suppression were not an option for free air engines, which had to be located in a location with high-volume air flow to cool the engine properly.

In addition, free air cooling was nowhere near as good at maintaining consistent engine temperatures as other cooling methods, depressing power output by as much as 30 percent as the engine got hot. And it just wasn’t as effective as other cooling methods in warm weather, either.

So liquid cooling began to replace free air as the cooling choice for performance sleds. A final and very crucial factor was when Rotax produced unreliable free air engines for Bombardier sleds, and that gave free air engines a bad rap that was simply not deserved by any of the other many brands that used it successfully.

However, the lower weight and cost of free air engines allowed them to stick around on economical and sporty trail sleds all the way to the beginning of the 1980s.

Deere Does It Two Ways

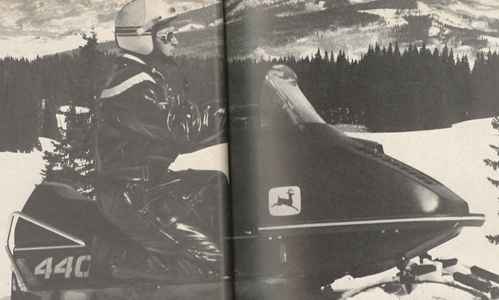

When John Deere introduced its new Sprintfire and Snowfire as mid-season 1982 models, they were essentially slightly enlarged and improved Spitfires capable of carrying two riders.

The more upscale Sprintfire had a liquid-cooled 340 with oil injection, while the price-leader Snowfire had a free air 340 that ran on pre-mix to keep cost down. This engine was actually the same one used in the revolutionary Spitfire, but with a Y-pipe exhaust header that was more efficient than the F-pipe header on the Spitfire. Therefore, the Snowfire engine made a little more horsepower.

The free air engine was combined with a nearly all-aluminum chassis to allow Deere to promote the 314-pound Snowfire as the lightest 340cc snowmobile on the market. This made the Snowfire easier to influence with body positioning while also being simpler to dig out when it was stuck and easier to trailer than competitive models. Deere also promoted less maintenance, pointing out that there were no fan belts to break on the light weight Snowfire.

At a good 20 pounds lighter and $500 less expensive at retail than the Sprintfire, the Snowfire also lacked its more expensive sibling’s standard equipment speedometer and warning lights. But both machines were positioned as trail sleds for family fun, including being particularly appealing for first-time buyers or smaller riders.

Factory fuel mileage estimates, developed on Deere’s dynamometers instead of out on the trail, illustrate one of the operational differences between these engines. The Sprintfire’s liquid-cooled engine was rated at 28 miles per gallon (MPG), while the Snowfire’s free air was rated at 22 MPG.

Realistically, both of these engines could do better under ideal conditions, and a 1984 Snowfire recorded 23.63 MPG in the second annual Snow Goer fuel economy tests, the best of any air-cooled twin under 400cc that was tested from any brand. But the Snowfire could also do much worse under adverse conditions like deep snow or mealy wet snow in above-freezing temperatures.

The Snow Goer team at the time had previously tested an essentially identical 1983 Snowfire and had some interesting comments.

“In test riding, we’ve found Deere’s long-travel suspension to be effective in absorbing some of the bigger bumps on the trail,” editors wrote. “On moguled sections, especially, it produced a smooth ride. The system is not as progressive as we expected it to be, however.”

Cornering was not viewed as favorably, though, due to less weight on the skis and the long-travel (for the time) rear suspension. The Snowfire was also inferior to other Deere models in deep snow.

Nevertheless, the Snowfire got a positive overall review.

“Surprisingly peppy at low end and mid-range,” our testers reported. “It’s a family machine with the emphasis on the wife and kids. Ideal as a second snowmobile.”

Others liked it, too.

“The Snowfire is fun to ride,” concluded Snowmobile magazine, which also noted that the relatively tall suspension was supple, plush riding and the equal in those ways to any other Deere model.

End Of The Trail

As a late-season introduction in model year 1982, the Snowfire was a full production model only for 1983. In a sign of things to come, Deere had a rebate on the Snowfire before the end of calendar 1982.

Deere and Company then sold its snowmobile business to Polaris in fall 1983, with fewer than 300 model year 1984 Snowfires actually built. Only a little over a thousand were built of all model years combined, making it Deere’s lowest production model aside from pure race sleds.

But the Snowfire was not just the least common John Deere trail sled, it was the last free air snowmobile in the entire industry, and as such it is actually a notably collectable model.

SPECS: 1984 John Deere Snowfire

Manufacturer: Deere & Company of Horicon, Wisconsin

POWERTRAIN

Engine: 339cc Kawasaki Heavy Industries Fireburst TB-340A free air cooled piston-port twin with one Mikuni VM-30 slide valve carb, Kokusan capacitor discharge ignition (CDI) and tuned pipe

Lubrication: Pre-mix at 50 to 1

Power output: 30 HP @ 5,700 RPM

Electrical output: 120 Watts

Clutches: John Deere/Comet 94C drive & John Deere reverse cam (outside helix) Ultra Form 80 alloy steel driven

Chassis

Type: Welded aluminum with Ultra Form 80 alloy steel steering protection plate, thermoplastic rubber (TPR) belly pan, sheet molding compound (SMC) hood

Claimed dry weight: 314 pounds

Front suspension: Mono-leaf springs with hydraulic shock absorbers

Rear suspension: Adjustable aluminum slide rails with torsion springs and one shock absorber on rear arm

Ski stance: 32 inches

Track: 15- by 116-inch molded rubber with riveted steel cleats and internal drive

Brake: Mechanical disc

Fuel capacity: 5.5 gallons

Oil capacity: 5 pints

Standard equipment: Adjustable handlebars, Kelch fuel gauge, passenger grab strap, glove box

Optional equipment: Speedometer/odometer, tachometer, handlebar heaters, halogen headlight, spare belt clip, backrest, tow hitch

MSRP: $2,599

I still miss the 70s and 80s sleds. All of the models were so much fun to ride and easy to work on. My last sled was a 1979 Arctic Cat el tigre 5000 and that sled was awesome! It took the beating that only a teenager can dish out and was always ready to go for more. Come home from a long ride, leave it sit in the yard, fire it up next afternoon and go. I also had a 77 Ski Doo Everest but it had clutch issues. My dad dealt with that, I was too young to understand