At the end of calendar year 1985, Mister Mister was on top of the pop charts with “Broken Wings,” Ronald Reagan and Michael Gorbechev had just had their first historic meeting, and the first production models of the Ford Taurus were hitting dealership floors. In snowmobile land? The biggest, baddest musclesleds of them all for the upcoming 1985-86 winter had between 521 and 597cc of displacement!

Don’t sell the 1986 Indy 600 triple, original V-max, up-sized El Tigre and robust Formula Plus short, however. These were some tough sleds aimed at serious customers. Let’s flash back to the December 1985 issue of Snowmobile Magazine, for which the incomparable CJ Ramstad penned the following article.

When Power Counts

Today’s high-performance snowmobiles deliver the maximum in everything – style, ride, handling, equipment – but let your thumb get a little twitchy and these eager hummers really shine.

In snowmobiling, performance is important. Whether you choose to hum down the trail on your 250cc single, a 340cc two-up family sled or a tricked-out 500cc trail modified, if you’re a snowmobiler, you care about performance.

And, when you’re riding in a group with your own kind, you can just about count on getting into a bit of friendly competition now and then. A little drag race maybe, a bit of throttle play down the trail, whatever. This is part of the sport… it’s fun and it gives us something to kid each other about when the day’s ride is over.

For some, however, the friendly competition aspect of snowmobiling can get a bit more serious. The snowmobile is a vehicle on which you can legally exceed 55 mph when you choose to and, for the competition minded, this is the equivalent of an open invitation to go for the maximum.

The manufacturers respect and appreciate their performance buyers. You high-performance snowmobilers know what you want, you expect to pay for the performance you are after and you generally select and purchase your newest snow-going equipment early.

The high-performance snowmobiles of today are much more than a big motor. To be sure, the powerplant is of primary importance when a buying decision is made. But a “musclesled” from any one of the sledmakers is a singular combination of qualities and equipment. All the muscle machines available in 1986 have unique personalities and each has an unmistakably individual approach to performance on the snow.

A TOUR OF THE ENGINE ROOM

Yes, most will agree the musclesled is more than motor. But power is still the first word in the performance enthusiast’s vocabulary and no report on high-performance in snowmobiling can properly begin with anything but a look at the whats and hows under the hood.

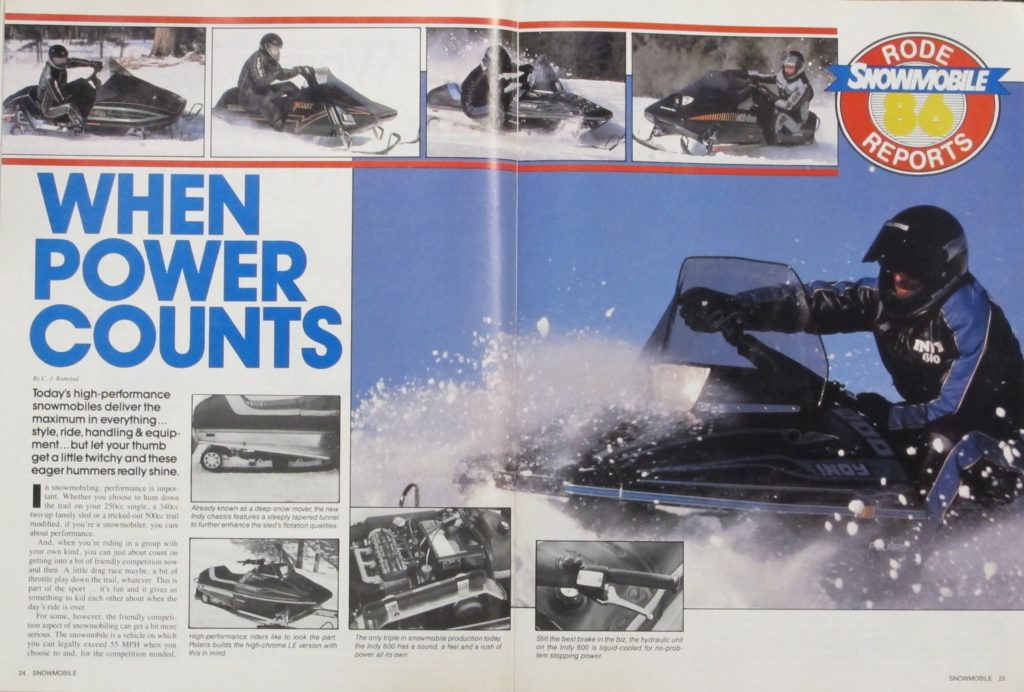

The big-inch title belongs, as it has for some years now, to the biggest Indy. Polaris’ 597cc triple is the only motor of its kind in production in snowmobiling today and those with experience riding the Indy 600 say the distinctive sound and incredible rush of power this three-cylinder liquid-cooled engine delivers are all the reasons you need to be Indy loyalists.

Steady updating and refinement of the big engine since its introduction has resulted in a civilized powerplant that offers reliability and a very acceptable service life along with unsurpassed output in terms of horsepower and torque.

Except for the unique three-cylinder layout, the engine is really quite simple and straightforward, featuring a three-into-twointo-one header, a single expansion chamber and a basic piston-port design.

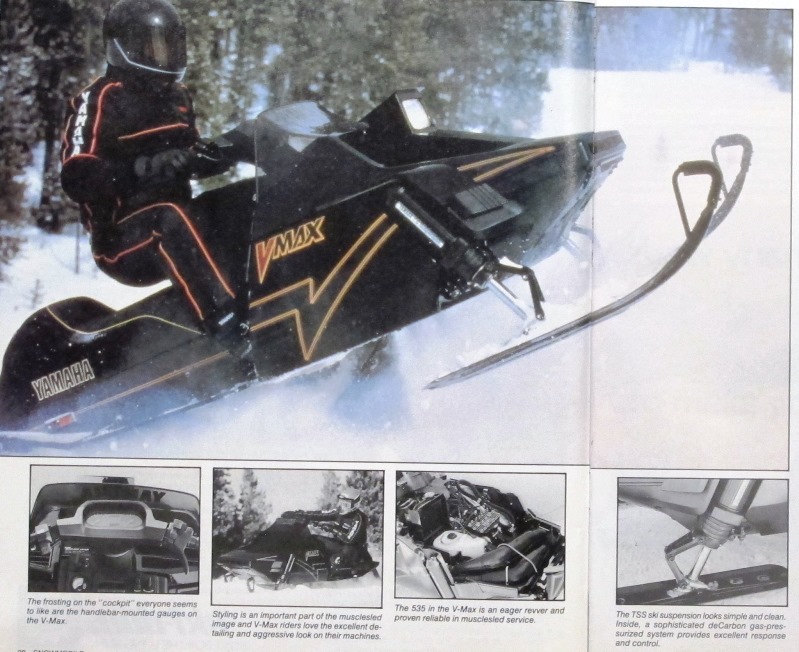

The next-biggest engine in this high-zoot performance class is the 535cc liquid-cooled twin in Yamaha’s V-Max. Another piston-port design, the compact powerplant is a very free-revving unit that makes the most of its beefy mid-range to be a true threat on the lake or trail.

Equipped with twin expansion chambers and the only slide-valve carburetors offered in the Yamaha model mix, the motor is satisfyingly throttle sensitive and eager to spin out the power off the line and all the way up to the 8200 RPM shift-out. Durability, an important factor in a powerplant asked to put out the maximum at least once on every ride, has been excellent since the sled was introduced and the proof is found in the fact that the V-Max has had only minor refining and up-dating in its years as the Yamaha Flying Flagship.

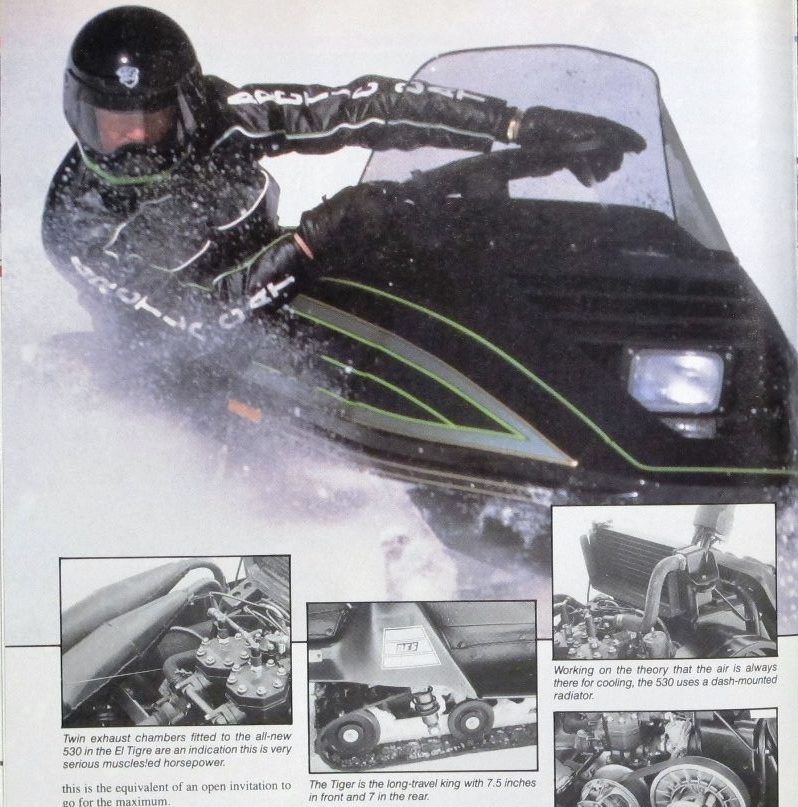

There is no substitute for cubic inches and Arctic Cat has scaled the new El Tigre up for 1986 with this important maxim in mind. Adding 30cc this year in an all-new 529cc liquid-cooled twin and going to two expansion chambers, a move rarely seen on sleds from Cat, the new El Tigre is very noticeably quicker off the line and through the lower mid-range this season.

Those devotees of the “Tiger” who stayed with the pack last year running the 500cc motor are in agreement the additional capacity will make this latest version of the classic El Tigre a very hard sled to beat in the “line ‘em up and go” game this season.

Equipped with Arctic’s now-familiar case reed induction as employed on high-performance engines from Cat in recent years, the new 530 pumps up the low end dig for ’86 and the heftier output all across the rev range is sure to satisfy the musclesledder who likes his performance dressed in black and green.

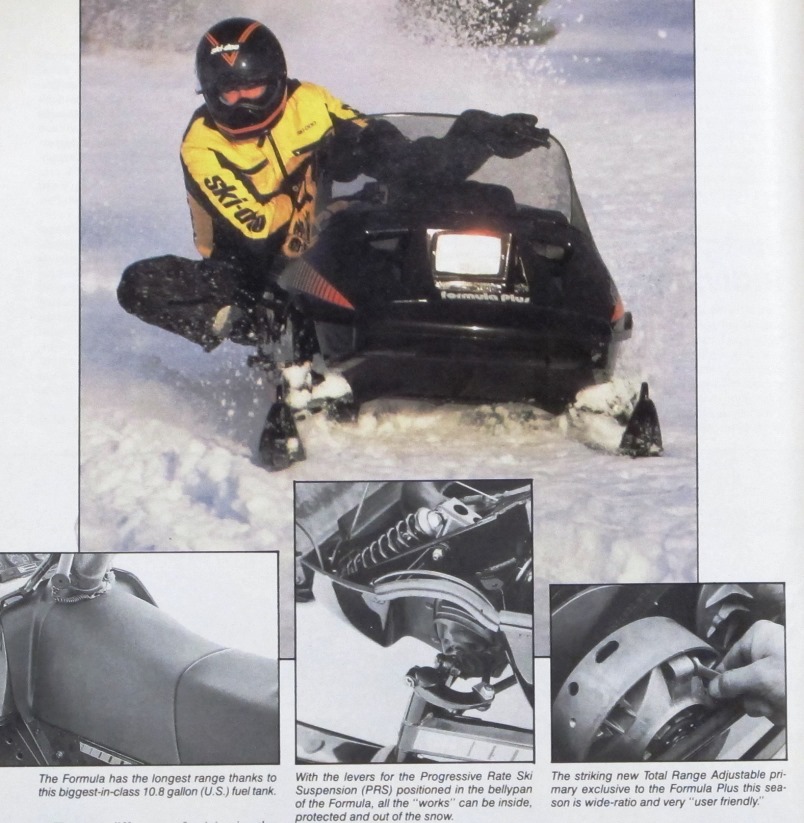

The smallest engine in the musclesled category in 1986, if “small” is a term we should use in relation to these high-output mills, is also the most sophisticated in terms of design. The 521cc liquid-cooled Rotax twin powering the Formula Plus in 1986 features the Bombardier exclusive rotary disk valve induction system running off the crank center PTO also used to power the liquid-cooling and oil injection pumps. A very precise system, the disk valve gives this biggest Rotax urgent power output across a wide RPM band and allows the 521 to perform with any of its larger-capacity brethren in the performance class.

The precision mechanically-controlled intake system allows the Formula Plus to run the biggest carburetors in the class, yet the fuel economy possible when the thumb is held in check is remarkable, especially when the awesome power this engine is capable of generating is taken into account. A single expansion chamber and free-flow aftermuffler keep things quiet while providing a noticeable “pipe” that gives the sled a satisfying boost in the upper rev ranges.

A RUN THROUGH THE GEARS

The other half of the power equation in a performance snowmobile is made up of the beltdrive, chaincase and track. Here the musclesleds provide four individualistic approaches that probably contribute most to the feel each exhibits on the snow.

The wide-ratio crown belongs to the Formula Plus in 1986 with the introduction of the all-new Total Range Adjustable primary. Engineered in Canada and constructed in the Austrian Rotax facility, the new TRA has the largest diameter in the class at 8.25 inches and a deep-sheave secondary completes the package to give the revised powertrain wider “gears” that translate into lower initial ratios and/or higher shift-out depending on owner set-up preference. Set-up is easy, too, as this breakthrough unit has external “clickers” that allow adjusting shift-out in 200 RPM jumps for precise and controllable fine-tuning . The secondary is also externally-adjustable, featuring easy-to-set bell height adjustment screws.

The Formula Plus puts the power to the snow with a 16.5 inch track, the widest in the class, and the relatively short contact patch gives the sled an agile feel at trail speeds that helps the sled deliver its characteristic effortless handling.

The P85 primary fitted to the Indy Six is a bit more familiar, having been introduced for 1985, and its 7.88-inch diameter produces an effective wide-ratio shift pattern that meshes well with the torquey output of the Indy’s big triple. A current favorite with the performance aftermarket and the hop-up artists, the P85 is tough, yet remarkably sensitive to RPM and perhaps the smoothest shifter in the sport today.

The biggest Indy transmits its ample power through a race-proven secondary to a 15-inch rubber track that shows the smallest contact area, or footprint, of the musclesleds, but this number is a bit misleading in this case due to the shallow compound bend Polaris uses on their sliderails to maximize deep-snow performance, a bend that results in a shorter measure on concrete.

The El Tigre and the V-Max both employ versions of the race-proven Comet primary, a high-performance veteran with a diameter of 7.5 inches. The most popular clutch in snowmobile competition today or ever, the Comet is known for reliable efficiency and true kindness to belts, particularly in high-rev, high power applications. Both of these machines feature that distinctive engagement and rush of power off the line that is characteristic of the durable and effective Comet design.

The Cat runs its exclusive easy-to-tune, easy-to service reverse cam secondary, measuring at l0.2 inches and transmits power to the snow through a 16-inch rubber track that helps the big Cat boast the biggest contact patch in the class. The V-Max displays the familiar 10.35 inch secondary employed on all high-performance Yamahas of recent seasons and a 15-inch rubber track that delivers a footprint right in the mid-point in the class.

RIDE, GLIDE AND SLIDE

Engine and powertrain specifications can help a musclesledder narrow down his final selection when it’s time to trade for a new powder rocket, but the ultimate decision nearly always rests on another criteria altogether … ride and handling. A snowmobile after all, high-performance or otherwise, has to feel right. The new performance machines all feature superb ride quality and taut handling, but each does the job in its own way, making one right for you, another right for the neighbor you meet down on the lake on that sunny Sunday afternoon this winter.

The Arctic Cat El Tigre introduced a new concept to snowmobiling that has been used with success for decades in the automotive world … the A-frame. Essentially a two-point supported radius rod system, the AFS used to suspend the skis on the new Tiger is light, compact, tucked out of the way and very effective.

By engineering the top A-arm to transfer movement inboard, the AFS delivers precise ski movement through 7.5 progressivelysprung inches. It’s a combination of razorsharp steering quality and plushness that has won many over since its introduction for 1985. The long-travel ski set-up is matched in back by a three-shock lever track suspension that moves 7 full inches, making the El Tigre the travel leader among the 1986 musclesleds.

Ski-Doo dove into progressive lever technology with enthusiasm on the Formula Plus, fitting both the track and skis with sophisticated coilspring systems that lend the snowmobile an in-control feeling on the trail unlike anything else available in 1986.

On the skis, the Plus uses trailing arms and radius rods that connect a pair of inboard shocks in a lever arrangement that’s very noticeably progressive in its action. Called PRS for “progressive rate suspension,” the SkiDoo design has the least travel of the muscle machines, but its progressive action gives the sled a supple ride and a “bottoAt the end of calendar year 1985, Mister Mister was on top of the pop charts with “Broken Wings,” Ronald Reagan and Michael Gorbechev had just had their first historic meeting, and the first production models of the Ford Taurus were hitting dealership floors. In snowmobile land? The biggest, baddest musclesleds of them all for the upcoming 1985-86 winter had between 521 and 597cc of displacement!mless” feel that’s very appealing, especially on a fast trail ride.

The track suspension is equally sophisticated. Utilizing three shocks, all connected by progressive levers, the design travels through 6 inches of total movement and displays the bottomless character typical of a well turned-out lever suspension. The most complex of the suspension set-ups in use in the high-performance category today, the Formula suspensions are also the most adjustable, featuring preload, position and limit controls at all necessary locations.

The V-Max was the first musclesled to feature a progressive coilspring track suspension and the veteran Pro-Action Link remains a very effective and comfortable unit still unsurpassed in ride quality despite remaining almost unchanged since its introduction.

Yamaha approaches the problem of suspending skis on a snowmobile in the unique way called Telescopic Strut Suspension (TSS). Looking very simple and uncomplicated on the outside, the TSS is really a very highlyevolved design utilizing remote gas pressurization and DeCarbon strut technology to produce a system that’s tough, effective and, externally at least, very simple and uncluttered. Thanks to the compact and self-contained TSS, the V-Max presents the smoothest underside to the snow of all the musclesleds.

The coilspring suspension revolution in snowmobiling was launched by the now-familiar Polaris IFS that’s the heart of the Indy personality. Starting out with about 4.5 inches of travel, the design has been refined and improved since first appearing in production in 1979 until today’s IFS on the Indy 600 features a full 6 inches of plush, compliant and controlled action. Despite advances made by the other makers in recent seasons, the Indy front suspension remains the supreme example of high-speed stability and confident trail handling in snowmobiling. Lighter and stronger today than when first introduced, the Indy IFS retains essentially the same layout and geometry that made the Indy a longreigning champion in cross-country racing.

The biggest Indy uses a coilspring/torsion spring combination to suspend the track, delivering a truly comfortable ride over even the gnarliest winter trail and working in combination with the ski suspension perhaps better than any other sled in this review. Like the ski suspension, the Indy track design has been developed over the years, extending its travel to the full 6 inches of movement available today.

JUDGING THE INDIVIDUALITIES

This is the trickiest part. Who’s to say which features and qualities are the most important? We’ve spent many hours with these machines as well as riding and talking with high-performance sledders, listening to their opinions and expressed attitudes about performance and the performance snowmobile.

In all these experiences, we’ve yet to sense any true agreement on what qualities are necessary in the Ideal High-Performance Snowmobile.

If your idea of a great musclesled is comfort and confidence at speed, for example, you might like the Indy best. Its long “wheelbase” and forward ski spindle location gives it wonderful stability. Part of this great stable feel, however, comes from the wide, low handlebars that some riders dislike because they get knee intrusion when they ride in the tight woods.

If your idea of the ideal musclesled is lithe, responsive handling on tight, narrow trails, you might select the Formula. The fast-rise progressive suspensions front and rear, the short contact patch and the fast steering all contribute to a sled that loves to be muscled … braked and accelerated and leaned … as it finds the quick way down the trail. Here again, some drivers say the firm feeling ride is “stiff” and the very characteristic Ski-Doo rider positioning with the angled-in grips, low windshield and long fuel tank is something that can either tum you off or on.

Many riders say they like a cushy ride and the Tiger goes the extra inch to deliver. This machine, when accurately set up with the springs to match the rider’s weight, can really impress with its bump-eating abilities. Its tall seat position, wide stance and slow-rise progressive suspensions contribute to this feeling. Some riders, however, told us they thought the long-travel sled was “too tall” and, as a result, less effective in the bumpier, higherspeed turning situations. The Tiger has adjustable handlebars, but we encountered some riders last year who said they couldn’t find the right position. We heard this about the Ski-Doo and Polaris, too.

Rider position seems to be an area where the V-Max shines. The sled has the lowest seat and a fairly high-feeling handlebar pivot point that nearly everyone seems comfortable with. The narrowest ski stance and absence of a swaybar give the sled a feeling of having very quick responses and many riders like the way the Max is sensitive to rider position inputs. Here again, what one rider loves, another dislikes. Some say they would not select the Max because they think it’s a demanding sled to ride at speed, and despite the easy steering and compliant ride, they don’t feel the at-ease control they enjoy on other high-performance models.

There are differences of opinion in other areas, too. We love the instrument position on the V-Max. but some riders say they don’’t like the dials “in their face.” We love the dash-mounted radiator on the Tiger, but we hear riders sometimes complain the thing spits melted snow on their visor under some conditions. We appreciate the brawny feel the big engine Indy imparts, but some riders say the front of this machine is (or feels) too heavy for all-day trail riding. We are fans of the extra-big fuel tank on the Formula for the range it gives us in unfamiliar riding areas where we can usually count on going farther and taking longer than we planned. The tank does take up space, however, and some riders find the position to be a bit intrusive.

The qualities these machines share in common – truly exhilarating acceleration, excellent trail behavior and prestige ride quality as well as all-around good performance in deep snow, ruts and hardpack – are exciting reasons to own a true high-performance snow mobile. The details are what keep it interesting, to our way of thinking. We’ve lived with all four of these honkers and love ‘em all. We have our reasons for our attraction to each one and, like the sleds themselves, they’re all different. Our oft-repeated opinion is, if you’re not already hopelessly brand-loyal, try to get to know the examples of the breed a bit before you make up your mind. There’s something fast here for everybody.

Editor’s Note: Every Snow Goer issue includes in-depth sled reports and comparisons, aftermarket gear and accessories reviews, riding destination articles, do-it-yourself repair information, snowmobile technology and more. Subscribe to Snow Goer now to receive print and/or digital issues.