In that dream sequence of events, you need the perfect machine — one that can take the punishment, has enough power, has handling that turns you into an expert rider and is light enough so you can control its every move. You need a true ditch-banger.

Whether you see yourself in that exact scenario or not, many people will be drawn to the 500 class Performance Specials.

In the recent past, we have evaluated musclesleds, the 600 and 700cc triples, and most recently, the solo luxury touring machines. Now that all four factories have a 500cc liquid performance machine for 1999, we couldn’t wait to pit them head to head and run them through some vigorous testing.

In slang, many folks refer to these sleds as “ditch-bangers.” They are characterized by their close relationship to 440-class race sleds, with high-performance shocks, race-style handlebars, high-output engines, topnotch brakes, seats with padded sides and (often) race replica colors. Even their names are taken from race sleds, with abbreviations tied to their racer mentality (MX for motocross, XC for cross-country, SX for snocross). These sleds are particularly popular in the Midwest, where ditch-line running and tight trails put a premium on lightweight handling. Their popularity is spreading rapidly, though. These are the machines that generate the most smiles and the widest grins.

Several issues are at hand with the four sleds in this head-to-head comparison. Owners of these sleds want industry-leading power-to- weight ratios. They also want handling that is spot on and the durability to ride hard.

We established criteria for the intended use of these machines and rated them according to what owners and prospective buyers are looking for. We looked at the suspensions and the handling. We evaluated the power and the clutching. We considered function and ergonomics.

And we crowned a winner.

THE VIGOR UNDER THE TRIGGER

A true performance special, whether in the 500, 600 or 700cc class, needs to have good power and light weight. These 500 class machines all have superb power-to-weight ratios and are high in the fun factor. With the horsepower and lightweight chassis that these machines possess, we wonder what more anybody could want. All of us agree that these machines would certainly have a happy home in our garages. Still, even though all of them perform well, they have differences, meaning we have our favorite engine of the four.

The Arctic Cat ZR 500 EFI’s 497cc case- reed liquid twin from Suzuki throws out 96 up making it feel more like a 600 class performer than it does a 500. The powerband is both instant and constant. From the holeshot to top- end, this engine just pulls and pulls. The throttle is responsive with the battery-less ER package, and through all of our rigorous testing the engine did not so much as burp. The power was constant to the track, thanks in part to the clutching. Whenever the torque load changed, the roller secondary sensed and adjusted to compensate without hesitation. Other than a slightly irritating exhaust note, we have nothing but praise for the Suzuki twin.

The new Polaris 500 XC SP’s U.S-built 500cc case-reed liquid twin with flat slide carbs carries tradition with the other two Polaris U.S.- built twins. The engine builds fantastic torque and horsepower, most notably and impressively in the mid-range. We noticed a slight hesitation in the XC at about 5500 RPM though. After that teeny weeny kink, however, this engine really hit like a sledgehammer and steamed all the way to the top. The clutching was not as responsive or as smooth as some of the others, but the tried and true Polaris clutching worked well at getting the power to the track.

During laketop testing, we found that the ZR and XC ran side-by-side forever. The Cat usually got the holeshot, but the Polaris would pedal up beside it in the 30 to 60 MPH range. Then they would spring off together until they reached top-end. The speedometers peaked out at more than 100 MPH, but the mid-90s is a more realistic evaluation of top-end.

Yamaha is certainly a welcome addition in this market. As with their other machines, Yamaha brought a smooth engine and clutch combination to the testing grounds. The 494cc liquid reed valve twin with flat slide carbs delivered power as smoothly as we have come to expect from Yamaha. The only problem was there just wasn’t enough of it. The engine was responsive, but the power was a little on the mushy side. It was obvious after riding the other machines, whether on the lake-tops or in the twisty trails, that you weren’t directing as much power with the right thumb.

While similar in displacement, this engine doesn’t seem to produce similar horsepower. Yamaha gets an A+ for smooth power, but we would like to see Yamaha give this powerplant a few more high performance tricks to differentiate it from the rest of its 500cc fleet. This engine is identical to the mill found in the Vmax 500.

The Ski-Doo was deceptive. Off the start, the Rotax 499cc twin with RAVE gave a surge, but the power soon tapered off when entering the mid-range and even more so on top-end. We were a little let down, because we often anticipate the Rotax engines to be the strongest. The Doo felt much faster than it was, hence the deception. Whether it was the riding position or poor wind protection, it felt like we were going faster than we were.

In our lake races, only the Polaris could keep up with the ZR. Our conclusion is that with the exception of the initial engagement of power, these machines are neck-and-neck in power. Why the ZR edged out the Polaris, though, is because the Arctic’s power was better managed. The Polaris’ power was well delivered, but not right at engagement. Sadly, by comparison, both the Yamaha Vmax 500 SX and the Ski-Doo MX Z 500 got spanked by these two machines when it came to power, quickness and speed. As mentioned, the Rotax plant surprised us. This is a relatively fresh engine to Bombardier, but it is an example of how fast this industry is currently moving it already needs an update.

All the power doesn’t mean a thing if the machine can’t be stopped. Finally, after a long awaited braking upgrade from Polaris, all of these machines have competitive brakes.

Polaris’ upgrade went to all of the Gen II Indys for this season, so the Indy 500 XC SP has it. Built by Hayes, the brake has a new master cylinder, caliper, lever, pads and a disc. The disc is designed to expand or shrink rather than warp in the temperature extremes.

The new brake has already been described as a “night and day” difference to their previous hydraulic brake. There is great feedback to the lever and the brake never showed any signs of fade. There was a wide range of use between the point where you initially begin to scrub off some speed to the point of full lock-up, a trait very welcome to a high performance trail machine. There is also good sensitivity in the travel range of the lever, so a few millimeters does a lot at the other end of the cable.

The Brembo dual-piston hydraulic braking system on the Ski-Doo is equally as responsive and predictable with fade-free control, but requires a little more effort at the lever. Still, going into a corner a little too hot is not large concern because good stopping power is a tug away.

The Yamaha brake again gets our praises as the best brake in the business, though, as mentioned, all the manufacturers now have good stopping devices. Yamaha’s Nissin brake is still the one to beat with effortless one-finger stopping power on the disc. The mechanical back up brake, too, is an idea we would love to see the other factories work into their systems.

The Wilwood stopping force found in the ZR is still a good system. Some claim it is the best brake in the business, but most of us at Snow Goer found that the lever travel is not as progressive as other designs. From the moment that the brake is engaged to the point of full panic stop is a short distance at the lever. Too short. Still, when used to it, it is a predictable and reliable system that doesn’t have the slightest problem bringing you down from the speeds this machine can reach.

THE BANG UNDER YOUR Bury

For these machines to even be considered a high performance trail machine there has to be leading technology under the seat. Not the foam material under the cover— we’re talking about the rear suspensions. No other component in a snowmobile has a greater effect on ride quality than the skid frame.

All four of the factories have different approaches to what they feel is the best rear suspension, and each one works a little differently. The method of our judgment was to simply try the different suspensions at various speeds and on various terrain until we had a good feel for what each suspension system was doing. Luckily, the site of Rode Reports in St. Donat, Québec, provided us with all the terrain we needed.

Yamaha’s ProAction Plus SX rear suspension system has the least amount of travel of the bunch. With rear travel at just 8 inches, Yamaha’s approach is to keep the ride height and attack angle low and therefore have a lower center of gravity for greater stability. In an era when long travel rules and everybody exaggerates their numbers to attract consumers, Yamaha went somewhat against the grain, but their system flat-out works.

What the ProAction Plus SX suspension lacks in travel inches it makes up for in quality. We have been fans of the ProAction system since its inception, and on this machine it rings true as well. The front and rear aim coupled suspension makes great use of its suspension range with help from the KYB aluminum-bodied high pressure gas shocks. The coupled arms in the suspension give the skid frame excellent communication for reacting to the different types of terrain. The suspension is progressive and only bottoms out on the big bumps, yet it does bottom out more frequently than the other three suspensions.

On the trail, the Yamaha skid frame behaves beautifully. The trail tremors are soaked up with only a hint of the suspension effort evident in the saddle. The compression cycle of the suspension is nice and progressive, with most of the impact gone if you happen to reach the stops when the plunger is all the way into the shock body. The rebound is quick enough that in trail chatter the suspension is set for the next hit by the time you get there.

In a mogul field that we found, Yamaha’s rear suspension was the best of the bunch. There was never a feeling of being on the verge of getting popped out of the seat. The coupled front and rear arms allow great communication for the entire system to work independently or as a unit for the different bump types. Most times, the front arm would bottom before the rear, and that was only under extreme duress. Yet despite the difficulty in bottoming, the suspension didn’t feel stiff or too soft.

Ski-Doo’s SC-b Cross Country suspension is great on a smooth trail or any terrain up to medium-sized bumps. If the 1 to 2 footers were the largest we would ever encounter, this would be an excellent suspension. It seems to have the smoothest rebound capability of all the suspensions tested in this evaluation. The rear setup with the HPG rebuild-able gas shocks has the perfect amount of sit-in, so there is a nice amount of travel on tap in case you cross a hole. The compression cycle of the rear shock is also nicely progressive, allowing high-energy impacts to disappear on the occasional big ones. The rebound is smooth, but sometimes the factory setup needed to be quicker.

In our field of rolling 2-foot and larger moguls, this suspension setup was caught off guard. The rear arm on the MX Z would compress to near-capacity, then return with a little too much force, often on top of the next one. The result when unloading at the top of the next bump would have the entire rear of the machine airborne, and the next hit on the front would thrust it back down. The teeter-totter effect is not control threatening, but it takes a lot out of you. With the MX Z, you need to plan your speed through this type of terrain carefully.

Arctic Cat’s FasTrack rear end with Fox gas shocks performs to its best potential in medium bumps at high speeds — believe it or not. The system is a little harsh in the small bumps, as the initial Fox shock movement is stiff, thanks to a stiff spring. The mid-stroke of the rear skid softens up, offering a great midrange stroke for a comfy ride in rutted and 1 to 2 foot whoop sections of trail. Because of the firm initial load, though, the suspension was not that pliant in the small stuff, or when riding at a slower pace in the medium bumps. This is another testament that this machine likes to be pounded on, and evidence of its race-inspired feel.

When riding this machine hard in the bumps, the suspension does better. The mid-range of the ZR was perfectly calibrated for aggressive riding in a bumpy setting, and in full attack mode this suspension shined. Once you passed the mid-range, the last bit of shock travel seems to get used up in a hurry, and the “thunk” of reaching the rubber stops is right there. The Cat rear would occasionally swap through a mogul field, though it was more controllable than some of the competitions’ kicks.

The Polaris XTRA- 10 rear suspension carries the Polaris Position Sensitive shock. It’s perhaps the industry’s best factory performance upgrade for 1999, yet it’s somewhat hidden. The Fox-built PPS shock has a specially calibrated ride zone for the shock’s mid-stroke. The system uses bleed holes between the inner and outer shock sleeves, allowing oil to escape for a more supple ride zone when trail cruising. When you encounter the big bumps, the piston at the end of the shock rod closes off the bleed holes and leaves the conventional shock valving to further diminish the impact of the hit.

After riding the XC SP, we can tell you that it really does work. The trail-tuned tide zone was perfect in our lake-top chop when we were encountering bumps of 6 inches to 1 foot. At varying speeds, the XTRA-10 rear equipped with this shock reduced the bumps to a mere vibration, not the kind of bump reaction that we had come to expect in a Polaris snowmobile.

In the biggest bumps of our testing, the Polaris XTRA-10 rear still shined, though not as brightly as the Yamaha. The suspension, or more so the shock, had great compression damping that was nicely progressive. When the skid hit the big bumps, the piston slid past all the bleed holes instantaneously and felt like a conventional shock.

However, there were some big hits that tossed our butts off the seat a few inches, meaning there was a violent reaction in the skid’s rear axle. The Polaris shared this trait with the Ski-Doo, where the suspension system would unload on the top of the next bump, thereby pointing the rear of the machine slightly skyward and the rider off the seat. Neither of these machines had the quickness in the rebound necessary to pound through a stutter bump or mogul bump section at higher speeds.

The coupled front and rear arms and the PPS shock really stood up to our torture tests and passed with flying colors. One of our editors remarked, “Unlike the ZR and MX Z, which have the attitudes of race machines, the 500 XC feels like an aggressive trail machine — there is still some plushness to the suspension, though you can still ride it hard.”

HANDLING SELLS IN THIS CLASS

The comfort end of every snowmobile is largely dependent on the rear suspension. How well the machine steers and handles as a whole is dependent on the front suspension and how the front and rear suspension act together as a whole.

We’ve said it before, and we’re about to say it again: Arctic Cat’s AWS V is the best-handling stock front suspension that this industry has ever seen.

The AWS V uses Fox gas shocks to control the 8.2 inches of bump-soaking travel. The independent A-arm design possesses the least amount of bump steer and scrub of any of the systems out there, and the compression of this system is fantastic right out of the box. The Cats that are equipped with the AWS V corner precisely and exactly to every touch of the bars. The front end also corners flat and never seems to push out from the line being held.

The front and rear suspensions are the best factory combination when it comes to weight transfer. On acceleration, there was excellent positive (rearward) weight transfer, aided by the Torque Sensing Link and the calibration of the FasTrack rear suspension. When we came off the gas going into a corner, the negative weight transfer was equally fantastic, placing the right amount of ski-pressure on the front end for successful cornering no matter the terrain or speed.

Coming out of a corner, a small amount of ski lift was noticeable. With the ZR, though, the ski lift never felt threatening. The outside ski held its line, the inside ski floated above the snow and off we shot. The ski lift felt more like an attribute to the ZR’s impressive power than it did handling miscue, although the wider-stanced Arctic Cat ZLs do corner flatter with the same power.

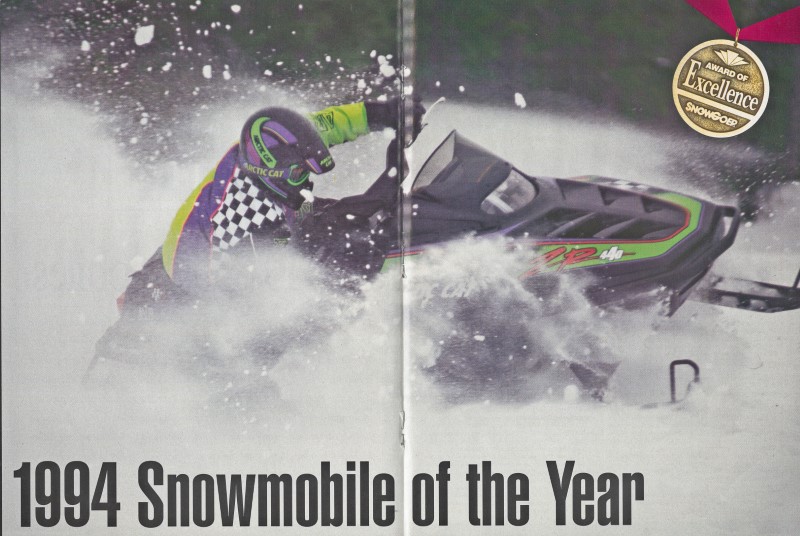

As a whole, the Arctic Cat had the best handling of the four machines we tested for this comparison. The combination of power, light weight and suspension calibration made us feel like a racer as soon as we took a seat.

The 500 SX has all the handling flick-ability that the other SXs have and a bit more:

lighter weight.

Riding this machine is an absolute thrill, with the cornering dexterity that this machine has built into the ProAction chassis. The confidence that the 500 SX gives is more than inspiring: it’s addictive. When entering a corner, the front and rear suspensions communicate to the rider in such a way that it is total rider involvement. The best way to steer the machine is to throw your keister a little to the side, hang the knee and let the sled do the rest. The thing about this machine that is different than the ZR, though (and the thing that is so addicting), is that it feels like you are the one doing it, not the machine.

The low ride height helps the SX remain the most stable machine of all four in the corners. The front end feels wider, further instilling confidence in being able to really speed through the twistiest sections of trail that we could put under the track.

Speaking of the track, we’ll say it right now: the 500 SX needs a new one. The hook-up just isn’t there. Rearward weight transfer and the aggressiveness of the track profile are two things that we would really like to push Yamaha into reworking as soon as possible. The front end has a little more aggressiveness to it than we would like to see, even when all the way on the gas. More rearward weight transfer is needed and we would certainly be happy with the .92-inch track found on the SRXs for this season.

The Yamaha’s front suspension is a trailing arm system that really does well at staying flat through cornering. Though the system does not use unequal length radius rods, the Yamaha does not feel like it exhibits a lot of bump steer or scrub.

What makes the suspension feel like it isn’t properly calibrated comes back to the weight transfer issue. The front end darts and chases many ruts in the trails, further evidence that there is too much ski pressure. The ski pressure does not seem to change when off the gas and on the brakes for a corner, though the steering effectiveness is super.

The Polaris Indy 500 XC SP is the best Polaris we’ve had the pleasure of riding. The XC- 10 front suspension with tipped-in trailing arms works extremely well with the XTRA-10 rear. The front end has the Controlled Roll Center geometry, meaning that it has unequal length radius rods that keep the skis flat while traveling upward through the suspension stroke and nearly eliminating bump steer entirely.

Like the other machines equipped with CRC, the 500 XC SP stays straight through the off-camber bumps and stays flat through cornering. Like the ZR, small amounts of ski lift were encountered, but nothing that would unsettle the rider’s confidence.

Like the rear suspension, this machine has well-rounded performance. Only slight darting was common to the front suspension, a trait more or less attributed to the aggressive ski design. Even though the front end would chase previous ski’s path, it never felt like it was leading you astray. Still, it can be annoying.

If Polaris chose a different ski design or reduced the amount of ski pressure with a limiter strap adjustment, they might lose the darting, but they would also lose some steering control. This is not a change we would recommend by any means. The steering feedback from the Polaris front end was bested only by the AWS Von the Cat. Polaris’ front end did not push in the corners, and whenever there was inside ski lift the outside ski held the line as true as you would ever expect.

There was a slightly looser feel with the steeling linkage in the Polaris, a trait some may prefer. One editor thought that the Cat’s steering was too tight, no doubt preferring the steering of the Polaris.

The Ski-Doo is the machine on which most of us had to adjust our riding style in order to really make it work. There is still evidence of chassis flex while cornering and on the gas, and there is still more ski lift than we would like. We would often have to lean way off the seat, shift our weight forward and pull down on the inside handlebar all at the same time to keep the ski low enough where we felt safe.

The front suspension did well in the bumps, but it seemed to have too much ski pressure, like the Yamaha. The front end had the annoying darting miscue and the steering was a little too aggressive. This is a change from last year that ended up being a trade-off.

Ski-Doo made an effort to correct much of the ski-lift for this year, which they have done with a shorter adjustment of the limiter strap. This limits the amount of rearward weight transfer slightly, keeping the center of gravity a little more toward the front, thereby reducing the amount of inside ski lift.

At the same time, though, the shorter adjustment of the limiter strap increases the amount of ski pressure and negative, or forward, amount of weight transfer. The added weight on the front also increases the steering effort and could be the cause of that pesky darting. Like we said, it is a trade-off.

Curiously, the shorter adjustment of the limiter strap did not seem to take away much of the hook-up capability of the rear end and the track. This goes against the norm, as typically you lose some rearward transfer with that type of adjustment.

If you are used to or enjoy the handling of a Ski-Doo, then this machine certainly fits the bill. To most of us it still feels like the front end is heavy and the chassis has too much flex. Its ski lift was higher and more frequent than the competition.

In the end, the Cat’s AWS V held its line in corners better and allowed us to switch lines in a corner most easily. Polaris’ XC-lO was just a heartbeat behind. The Yamaha front suspension sucked up bumps the best but it would drift slightly in corners. The handling offered by Doo’s DSA Plus was a distant fourth.

MAKING THE PILOT COMFORTABLE IN THE COCKPIT

It is consistently the little things that matter. Take the best handling machine on the face of the planet, and if there is an unwelcome feeling in the seat it is nothing you would want to spend a lot of time on. We always put substantial value in the controls, location, rider position, seat quality and other cockpit features. Yup. It’s the little things that make for a real winning machine.

Polaris made big changes to its ergonomics this season. All-new handlebar controls are now just a thumb-length away. Your left thumb is in charge of the high/low beam lighting switch and the hand and thumb warmer controls. All of the switches are within easy reach and in a don’t-have-to-look-down location that is functional and practical.

For taller riders, though, the bars themselves are not in a good location. Long legged riders who ride anywhere but the very rear of the seat may find the handlebars in the knees. Polaris did raise their bars slightly and added 1 inch to their length, but our knees still found the bottom of the bars a couple of times.

The seat is all-new from Polaris and is their greatest effort. Their seat cover is easy to move around on and the design is functional for aggressive riding. It is sculpted nicely to the tank and the material under the cover is about the right density for solid firmness without sacrificing comfort. The seat’s side-pads taper well into the design and have a decent thickness. You shouldn’t ever have the tunnel edge jab your tailbone when hanging off on a long sweeping corner and hitting a bump somewhere in the middle.

The flared windshield looks small and works well into the design. More importantly, it offers great wind protection. The footwells are not-too-tight, not-too-loose and the fit and finish is much improved over the expired Indy design.

The Arctic Cat’s ergos make us feel like a racer the moment we are in the saddle. The bars are wide, straight and tall. They also have the controls for the high/low beam and the handwarmers away from the grips, giving hands more room for the cornering work, but they require letting go to flip the switches. The seat cover is nice and slick, conducive for sliding around on in the corners. The seat and tank are also sculpted well for the ability to get close to the middle of the sled to keep weight central for hard cornering, and the straight bars are mounted such that they won’t get in the way.

The seat sidepads are attractive and functional if you are all the way off the seat and hanging on the side, but if you are anywhere in between, the pad edges protrude into your rear. They should be tapered more into the seat for more comfort for those who aren’t quite cornering with Kirk Hibbert speeds.

The footwells on the Cat remain loose. We like our feet to feel somewhat held by the footwells, so we have the feeling of a last chance ankle-save if we are about to get tossed from the machine and our hands have become dislodged of their grip. Behind the windshield, the upper body protection is good, but there isn’t much protecting the hands. Expect to use the handwarmers on high more often with this machine.

The Ski-Doo ergos also have mixed reviews. Most of us liked the riding position and loved the fact that our entire foot can be in the footwell at a nice angle. The handlebar positioning is good, and like the Cat, there is room to get nice and close to the tank if it suits your riding style.

Ski-Doo’s fit and finish is closing in on Yamaha’s quality, and the design is still very attractive. The windshield offers little protection from the wind, which is a chilling factor to consider.

What doesn’t work at all is the seat. The seat firmness is the softest, and it is comfortable for trail cruising. What needs to be discovered, though, is that the MX Z is not a trail cruiser! The seat is not only too soft, but the material is something that has got to be changed. The four-way stretch material might be durable, but it makes the actual riding of the sled a chore. Rather than being able to slide across the seat, you are forced to pick yourself up and manually shift yourself over to keep your weight inside. Do this for an entire day on the trail and you’ll be tired sooner than if riding any of the other three. This is another example of how riders have to alter riding habits when mounting this sled if they are not everyday Ski-Doo pilots.

Finally, the Yamaha’s ergos are about the best to be found. The seat is very well sculpted and has a great firmness to it. The 5-inch gauges are a nice addition, though still not the easiest to read and the handwarmers have the widest range of temperature adjustability. Most of us like the footwells, though some larger-footed editors commented that they were too tight.

Still, you can’t have the perfect ergos for everybody. The windshield looks great, but protects little. The seat that is great in length, firmness and design is a bit on the sticky side, though not as bad as the Ski-Doo’s. The hand- warmer switch is hard to find, and we almost had to pull to a stop to operate it. The handlebars are angled, and though they are good with function, they don’t have the high performance feel of the other three machines. The Yami also has the best grips, although they can make mincemeat out of your hands if you’re riding with thin gloves. While we were able to find minor flaws in this machine’s ergos, it was the sled of choice for most of us in terms of comfort.

JUDGEMENT DAY

Never in the history of Head To Head comparisons have the votes, opinions and competition of the four sleds been so close. Picking a winner was a really tough business, because as we have said, any of these machines would be welcomed in our private garages.

However, we have the guts to name a winner. After countless hours of bickering, name- calling, hair-pulling and finger pointing, we put our personal differences aside for a few hours and attempted to calmly decided a winner and the runner ups. But, inevitably, the fighting started again.

After all the arguing subsided, we crowned the ZR 500 ER the winner of this year’s Head To Head.

The reason this sled edged out the others is because we feel that it best suits what this class represents. The 440cc liquid race specials are basically gone from the showroom floors, and these are the models that have taken over that position.

We feel that the ZR is the mightiest performance machine in the group. Its high-horsepower engine, racer ergos, aggressive suspension and impeccable cornering control make this the perfect sled to bash around in the ditches, scour a laketop or carve through a groomed trail.

Both the Polaris and the Yamaha were just a tiny bit short of the mark.

The 500 XC SP’s only real downfall is having to be compared to the other sleds. On its own merit, this sled could win all sorts of awards.

Its powerplant is a close second place because of the initial burp that is often encountered at the start of the mid-range, where this engine really comes on strong. The ergos are marred only by the low handlebar positioning, though it is an important factor. The rear and front suspensions finished second in their respective divisions, making this a good combination sled.

The Yamaha Vmax 500 SX is also second place material instead of a champ for a few key reasons. We already talked at length about the lack of power that the SX has compared to the others in the class. But we can’t cut it short for just one simple reason, even though it may be a big one.

The weight transfer and traction still leave something to be desired. The machine feels like it would go faster if the power was biting the ground. If they started by throwing the new SRX track on the SX line for 2000, they would really be on the way to something great. A reworked rear end for better weight transfer and a little more juice and that outcome might have been better.

As for the MX Z 500, most of us sadly believe that the machine is already dated. The power was not at all what we would expect from Rotax. The trail and high performance riding ability are more than adequate, however, and once adjusted to the riding requirements of the Ski-Doo, it could certainly win cross-country races —just not a victory in our Head To Head comparison. A change to the ZX chassis and uncovering some unused horsepower in the engine would really please us. Oh — and if they changed that seat material.

In the final evaluation, the ZR best met the bad-to-the-bone nature of this class. The SX would be the best pick for somebody who wants the best ride quality from their buggy, while the XC would be a wise choice for somebody who wants more power, new looks and a very solid ride. The MX Z, by our standards, is a step behind.